221B Baker Street is an investigative game set in Victorian London with crossword-like puzzle solving and game play inspired by Cluedo. This is classic Conan Doyle, with Holmes trudging around London with a magnifying glass, solving cases by putting together the pieces. The version I reviewed was the 2014 re-release, presumably put out to capitalise on the explosion of Sherlock Holmes-related media from 2010. But neither Doctor Strange nor Iron Man appear in this version, which sticks very close to the popular pipe-and-deerstalker image of Holmes. Alas, the design fails to live up to the flavour, suffering from uneven pacing and poor social interaction.

• Designer: Jay Moriarty (Antler Productions)

• Publisher: Gibsons

• Number of Players: 2-6

• Playing Time: 60-90 Minutes

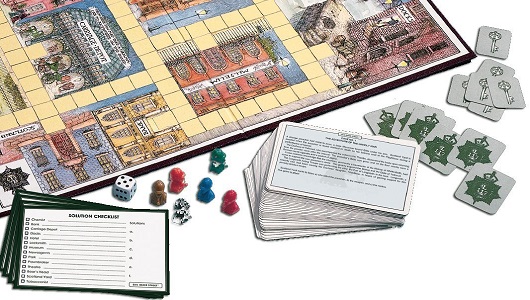

As competing Sherlocks, each player begins at the eponymous 221B Baker Street and meandering through London, accumulating clues. The players are given a case to solve (there are 75 in total) and are looking for the answers to several different questions, typically of the who-what-when variety. Each location contains at most one clue. These clues are sometimes textual descriptions of facts, and sometimes crossword-style puzzles whose answers provide part of the correct answer to one of the game’s questions. The first player to solve the puzzle and return to 221B Baker Street with the right answer wins, though if their answers aren’t quite on point, the game continues.

Travel occurs one die roll at a time, moving 1-6 spaces along the streets of London. Players can manipulate the rooms by “locking” an entrance to a location using Scotland Yard to cordon off the area. Players can open police-locked locations by expending a key, obtained at the locksmith, implying that corruption in Victorian London was terribly severe. There is also a carriage yard from which you can take a Hansom cab to travel instantly to any location.

The cases I played were competently fleshed out in terms of story, and the puzzles themselves are well enough designed. The engages players’ deductive skills directly through clues, rather than abstractly as in Cluedo, which is a good fit for the Sherlock Holmes flavour. The designer, the uncannily named Jay Moriarty, clearly loved the detective genre, and wanted to bring the investigative experience to life. Nevertheless, the game is weighed down by avoidable design flaws. It feels old, like it needs a bottom-up redesign, not a re-release. The first edition of the game was published in 1975, decades before the great Euro-game revolution in design. The problems that sap the life out of the game boil down to two: the poor pacing, and the lack of social interaction.

Most turns are nothing more than roll-move-go, which takes barely ten seconds. When you enter a location, you get to look up a clue in the booklet, for which you are allocated 30 seconds. The result is that the booklet is in constant demand, with turns flying around the board faster than a single player can read their clue. This creates pacing problems on both sides, giving the impression that the game is moving too fast, and yet crawling along too slowly. An unlucky streak of rolls can leave a player out of the game for five or more turns with nothing to do at all. This is very poor design that disengages players from the game. Adding a 2nd die to the roll would have improved matters, and eliminating the dice and spaces entirely would have been better.

Detective work is quiet and lonesome. Puzzle solving works against chatter, as players need their focus to collate clues. Play proceeds in monastic silence, without any method of consulting or interrogating other players. The locking and unlocking mechanics are the only directly form of interaction. But since every player starts with one lock and one key, the blocking game is mostly irrelevant. It is rare that a single location is critical to an investigation, and even if it is, the player doing the blocking could not possibly know that, and so they can’t use it very strategically. In the rare event that a lock prevents a player from accessing an area, the optimal response seems to be to simply ignore it and go around. On an efficient circuit of London, each player visits each location at most once, and would be crazy to spend a dozen turns getting a second lock or key – so much for only social mechanic.

While some clues are themed by the location, there isn’t a consistent relationship between locations, clues and cases. The scene of the crime may sound like a good place to begin an investigation, that isn’t a necessary step, or even a particularly good first move. Efficiently searching locations is a matter of finding the shortest path, something which does not change from case to case, and undermines both intellectual engagement and replay value. The textual clues are flavourful and sometimes clever, but the puzzle clues erode the immersion. For instance: “The General was bad tempered and disliked by his neighbours” is the sort of clue Sherlock might uncover, whereas “WEAPON CLUE: A pretence followed by a hurtful piece of glass and a bottle stopper” is the sort of clue one might find in the Sunday crossword, but not at a crime scene. The match between the Conan Doyle theme and the investigative mechanics is one of the game’s virtues, and it would have been better had they followed the theme through.

Overall, 221B Baker Street is an interesting idea for a game, but far less fun than it should have been. Nobody I play tested this with was eager to play again. Aficionados of puzzles and mysteries might find something to like, especially if player interaction is not a priority. Die hard fans of Sherlock Holmes might enjoy the investigative flavour and Victorian setting. But I can’t recommend it in general. If you’re in the market for a competitive Cluedo-like game of investigation and deduction, I’d suggest picking up Mystery of the Abbey. If it’s puzzle solving you want, pick up an escape room in a box, like Exit: the Game, or Unlock!